MMT and Treasury Debt Payoff Part 1 of 2

In that great deliberative body (formerly) known as Twitter, I have been arguing with several fans of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Specifically, several of them were claiming that it was ludicrous for fiscal hawks to worry about the federal debt. “Don’t these fools realize”—so the MMTers argued—"that if the government ever paid off its debt, then the supply of dollars would shrink to zero?!”

I tried several routes to get these folks to realize that their claims were simply wrong. (In fairness, I had some MMTers tell me that “no serious MMT scholar” believed the claim, and that I was picking on random guys on Twitter.) It will be instructive to walk through the arguments here at my infineo platform, because the whole exercise sheds light on how our modern financial markets work.

As a last housekeeping note: I’m splitting this topic into a two-part series. In today’s post, I’ll give some screenshots from my Twitter brawl but also some quotes from leading MMT gurus, to explain where they’re coming from. Then I’ll give some quick demonstrations to show that something has to be wrong with their argument; if the Treasury began aggressively paying off its outstanding debt, this wouldn’t reduce the money supply by one penny.

However, after I go through all of that and hopefully convince you, dear reader, that the MMT people were full of it, I’m going to admit something shocking: Way back in 2010, I myself wrote an article that seemed to be saying the same thing as today’s MMTers! So I’ll wrap up today’s post with that cliffhanger, and then next week (in Part 2) I’ll get into the more complicated machinery of Fed operations, to show the connection between the central bank and Treasury debt.

Why Some MMTers Argue That Paying Off the Treasury Debt Would Eradicate the Dollar

I won’t bother screenshotting and linking to all of the various streetfights I’ve been in the last few weeks, but let me at least give a flavor of the fantastic beasts you may find when you wander into MMT land online.

The guy that kicked it all off was endorsing MMT guru Stephanie Kelton’s book, as shown in this first exchange:

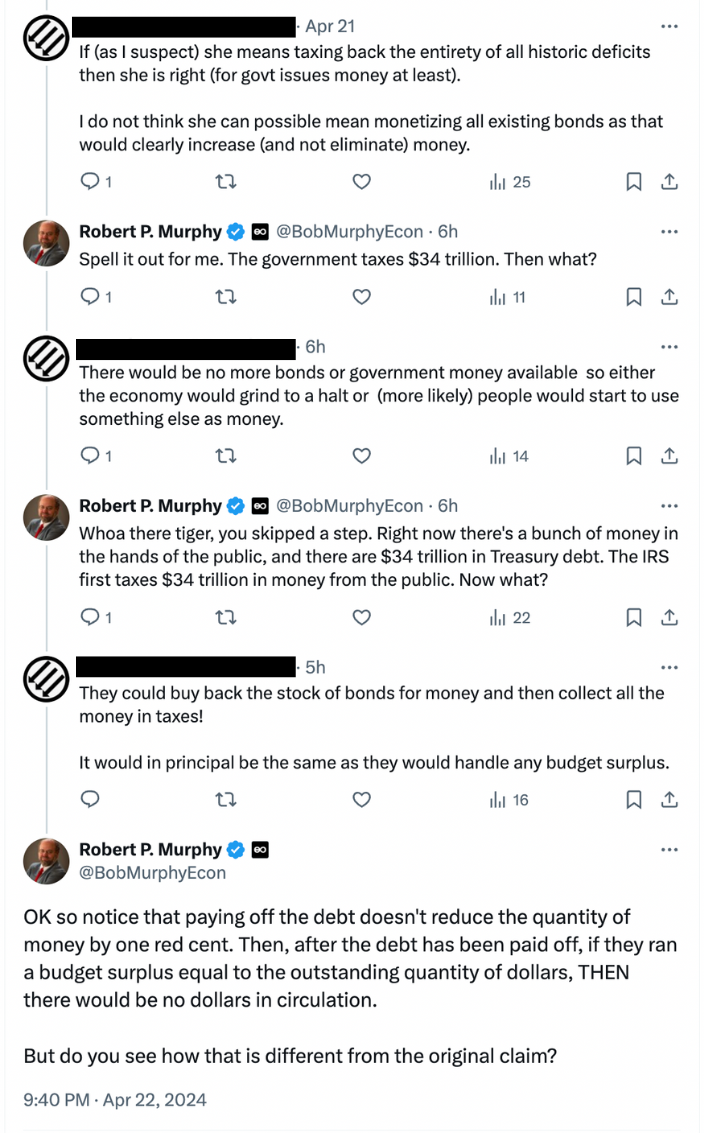

Then, in my opinion, I backed that guy into a corner and he walked away. When I summarized the battle in a new thread, I had another guy jump in and test his stamina:

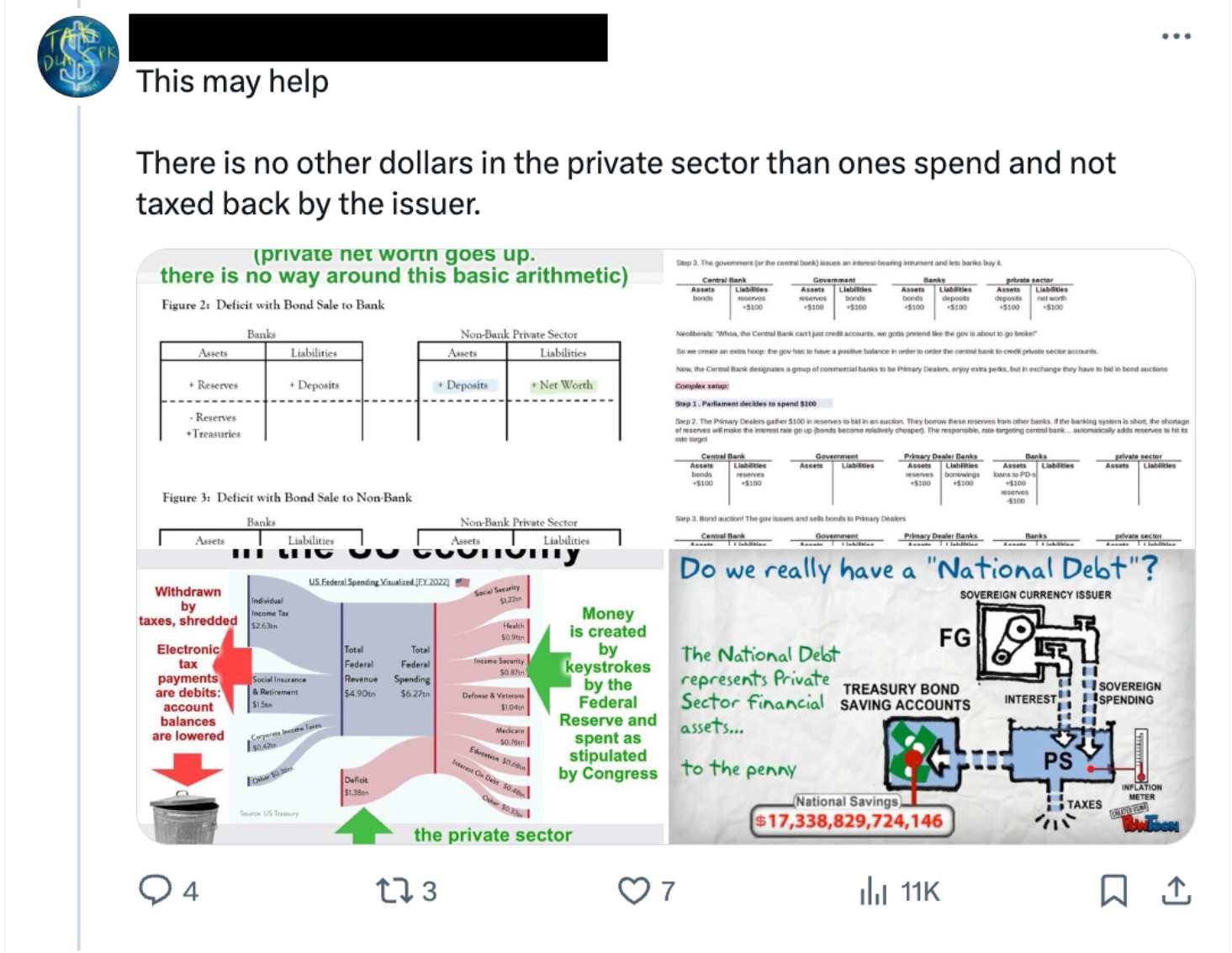

One might have thought this would settle the matter. But no, yet another MMTer jumped in, this time with visual aids:

And of the above, the following is the most pertinent to the discussion:

So the above screenshots certainly establish that at least some fans of MMT believe that paying off the outstanding Treasury debt would eliminate the supply of dollars. (To be clear, we are here talking about legal tender US dollars issued by the US government, which includes paper currency as well as bank reserves on deposit with the Fed. We’re not talking about commercial bank-issued claims on legal tender dollars, even though these are included in some monetary aggregates and can count as part of “the money supply” in certain settings.)

But let me sympathize with the rank-and-file MMTers and say that their position naturally flows from what their leading gurus have written. For example, as I quote in my review of her book The Deficit Myth, Stephanie Kelton explains how one of the founding fathers of MMT, Warren Mosler, rejected economic orthodoxy and rediscovered the (ostensible) insights of the chartalists:

MMT rejects the ahistorical barter narrative, drawing instead on an extensive body of scholarship known as chartalism, which shows that taxes were the vehicle that allowed ancient rulers and early nation-states to introduce their own currencies, which only later circulated as a medium of exchange among private individuals. From inception, the tax liability creates people looking for paid work…in the government’s currency. The government… then spends its currency into existence, giving people access to the tokens they need to settle their obligations to the state. Obviously, no one can pay the tax until the government first supplies its tokens. As a simple point of logic, Mosler explained that most of us had the sequencing wrong. Taxpayers weren’t funding the government; the government was funding the taxpayers. (Kelton, pp. 26–27, bold added)

And then to connect this notion of the government “spend[ing] its currency into existence” to the worries over the national debt, later Kelton writes:

The truth is, we’re fine. The debt clock on West 43rd Street simply displays a historical record of how many dollars the federal government has added to people’s pockets without subtracting (taxing) them away. Those dollars are being saved in the form of US Treasuries. If you’re lucky enough to own some, congratulations! They’re part of your wealth. While others may refer to it as a debt clock, it’s really a US dollar savings clock . (Kelton, pp. 78–79, emphasis in original.)

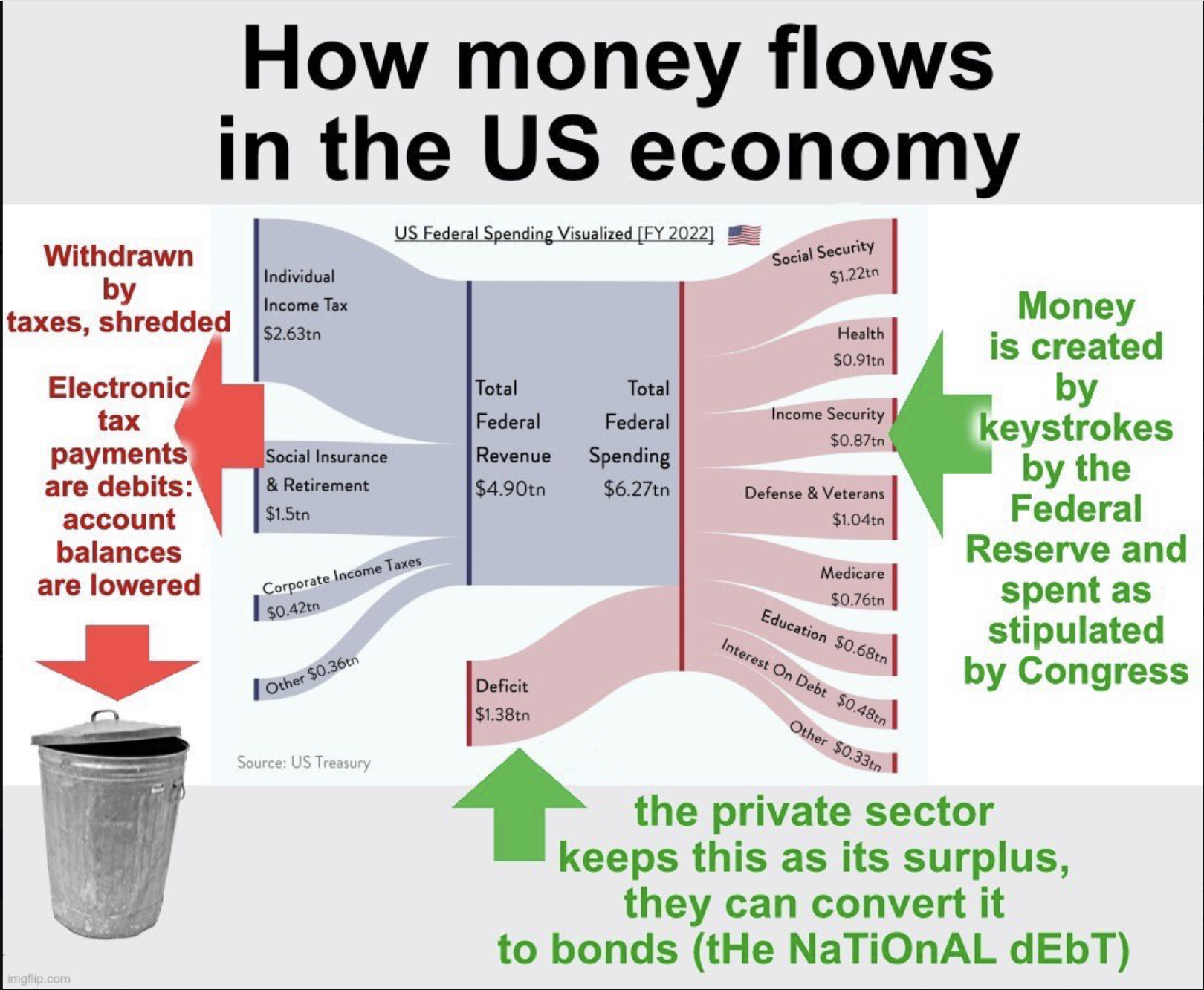

With this background, the claims made by my Twitter antagonists should make more sense. The MMTer believes that US dollars came into existence through the federal government spending more dollars than it taxed away. This follows from their method of accounting: In the very act of spending money, the US government creates new dollars and adds them to the public’s holdings, while in the act of taxing money, the US government destroys those dollars when removing them from a taxpayer’s possession. Therefore, at any given time, the total quantity of US dollars held by the public must necessarily equal the net excess of US government spending over US government taxing since the start of the country.

But at the same time, we also know from standard accounting that if we’re going to apply conventional fiscal metrics to the US government, then when it spends more in a given year than it takes in through taxes, the difference is called the annual budget deficit and it adds to the federal debt. But if the federal debt is simply the historical tally of how much the government spent, over and above how much it collected in tax receipts, then that must be the same number as the quantity of net dollars injected into the economy.

Now even here, as I’m trying to bend over backwards to be fair to the MMT camp, there should be some cognitive dissonance: Is the government’s excess spending over taxation equal to the quantity of dollars or to the outstanding Treasury debt? It seems it should be one or the other, but not both. Kelton seems to be vaguely aware of this issue, when she writes in the second block quotation above, “Those dollars are being saved in the form of US Treasuries.” Also, if you scroll back up and look at the detailed money flows in the MMT-approved diagram, it says of the public’s surplus that “they can convert it to bonds (tHe NaTioNal dEbt).”

In any event, I hope I’ve at least done my duty as a fair combatant, to explain where the MMT people are coming from, when they argue that paying off the federal debt would eliminate all the dollars.

Now, in the next section, I will quickly show why this reasoning is wrong.

Why the MMT “Logic” Is Obviously Flawed

Currently, the amount of US Treasury debt is over $34 trillion. (As of this writing, if we rounded, it would actually be closer to $35 trillion.) So the question is, if the Treasury were to redeem all of this outstanding debt, what would happen to the quantity of US dollars in existence?

Well one way to do it would be for the federal government to simply create a new $34 trillion in money, and use it to buy back all of the Treasury debt in a simple asset swap. This shouldn’t pose any angst to the MMT crowd. After all, arguably the single most emphasized among Kelton’s talking points is that we don’t need to worry about servicing the federal debt, because the Fed can just create more dollars.

So if the Fed simply created $34 trillion in new money and used it to retrieve all of the existing Treasury debt, that would solve the problem of the federal debt. (At least, it would eliminate the debt if we view the Treasury and Fed as a consolidated budget entity, which MMTers clearly do.) So if that’s the route by which the government pays off the debt, did it eliminate all of the money?

No, obviously not. In fact, it added $34 trillion in new dollars to the economy.

OK, but in fairness that’s not what a fiscal hawk means by “paying off the national debt,” and so we can go through a more conventional approach. Suppose the government taxes (say) $100 billion away from the citizenry, and then uses that $100 billion to buy back $100 billion of Treasury debt held by the citizenry. In terms of public finance, this would be scored as the Treasury running a $100 billion surplus for that period. The national debt would go down by $100 billion. And the quantity of money held by the public would be unchanged—the IRS took $100 billion from them, but then the Treasury gave the money right back when it retired the bonds.

So I’ve just shown that the government could reduce the Treasury debt held by the citizenry by $100 billion, and this wouldn’t affect the money supply by a single penny. Now just repeat that process until all of the Treasury debt held by the citizenry is extinguished. The government runs a surplus equal to the entire amount, the national debt falls by that amount, and the public ends up holding the same quantity of US dollars that it held at the start.

At this point, I’ve used pretty straightforward arguments to show that whether it used monetary or fiscal policy (i.e. the printing press or the IRS), the federal government could withdraw all of the Treasury debt held by the people without changing the amount of US dollars held by the people. So the MMTers I quoted above clearly have a flaw in their reasoning.

Uh Oh, a Monkey Wrench in My Demonstration

After going through the above type of arguments with my Twitter belligerents, I was feeling pretty good about my position. However, I had a slight pang of doubt because I knew that the Federal Reserve bought Treasury debt in order to issue more “reserves” or “base money” to the banking system, which the commercial banks then used to pyramid their own loans and create even more “dollars” in the broad sense.

This is why, in my arguments above, I used the perhaps odd-sounding terms of “the citizenry” and “the people,” rather than the more familiar phrase “the public.” The reason I did that is in conventional accounting, the federal debt “held by the public” excludes intragovernmental debt such as the Socal Security trust fund, but it still includes the Treasury securities held on the Fed’s balance sheet. (This is because the Fed it a quasi-private institution with nominal independence from the federal government; it’s not an agency of the feds the way the Social Security Administration is.)

Now don’t get me wrong: The MMTers aren’t allowed to invoke Fed-held Treasury debt as their escape clause, because they view the Treasury+Fed as a consolidated entity. But still, I knew there was possibly more to the story than my quick assault in the above section.

Alas, my vague uneasiness was heightened when someone on Twitter remarked that he had thought the classic right-wing conspiracy book, The Creature from Jekyll Island, itself endorsed the view that our financial system was based on debt, and that if all the debts were paid back, we’d run out of dollars. I agreed with the person saying this, and dug up my old 2010 article where I spelled out the logic of G. Edward Griffin. As I skimmed my old piece, I came across this bombshell line near the end: “[I]f people in the private sector ever paid off all of their debts, and the federal government paid off all of its bondholders, then the supply of US dollars would be virtually extinguished.”

Yikes! Does this mean the MMT people were right after all?! Or was I myself a fool back in 2010?

Fortunately for my pride, I think I can reconcile the apparent contradiction. That is to say, if I spell out the logic of what I was arguing back in the 2010 piece, we will see that it’s not justifying the claims made by today’s MMTers. Even so, this is obviously a nuanced topic, and so I’ll wait till next week to give the complete reconciliation of the various strands of the argument. To fully understand the relation of Treasury debt and US dollars, we have to consider how the Fed operates, and also analyze the actual history of the dollar—rather than the armchair reasoning from the MMTers.

In conclusion, it’s rather ironic: The MMTers like to pride themselves on describing “how the world actually works,” and they typically mock the Austrians for their “a priori” reasoning and moralistic aversion to government fiat money. But in this instance, it is the MMTers who are refusing to acknowledge reality, ignoring common sense and basic history. But we will have to wait till next week’s post for me to spell all of this out.

NOTE: This article was released 24 hours earlier on the Infinite Banking (IB) 3.0 - The Future of Finance Group

Dr. Robert P. Murphy is the Chief Economist at infineo, bridging together Whole Life insurance policies and digital blockchain-based issuance.

Twitter: @infineogroup, @BobMurphyEcon

LinkedIn: infineo group, Robert Murphy

Youtube: infineo group

To learn more about infineo, please visit the infineo website

Comments