Whole Life Insurance vs. Zero-Coupon Treasuries

In this post, I’m going to argue that standard financial analysts have given Whole Life Insurance a bad rap when it comes to its expected rate of return. Specifically, the standard figures thrown around for the (alleged) “average return” in a Whole Life policy make assumptions about surrendering the policies early on.

Yet this approach isn’t how we would evaluate other (hypothetical) assets that had similar characteristics as a Whole Life policy. To illustrate, in this post, I will walk through various scenarios to see how we would evaluate hypothetical assets in them, which will then make my point that Whole Life has gotten a bad rap.

Scenario 1: A 25-Year, Zero-Coupon Treasury

Right now the US government offers various bonds with different payback characteristics. For example, a T-bill that matures in (say) 6 months doesn’t carry a coupon payment. The investor buys the bond at issuance at (say) $970 and then, six months later, redeems it with the US Treasury for the face value of $1,000. The original discount on the purchase price implies a 6-month return of ($1000-$970) / $970 = 3.1% rate of return, which works out to an annualized net yield of 6.3%.

When people want to buy longer-dated Treasury bonds, however, they typically want to receive a flow of “coupon payments” along the way, which represents the periodic interest payment along with the return of principal at maturity.

However, there do exist long-dated zero-coupon Treasuries (sometimes called “zeroes”). For example, a new zero-coupon Treasury security promising the bearer $10,000 twenty-five years in the future, in 2049 —with no other payments along the way—might be auctioned off today in 2024 for (say) $3,440. Because of this original issue discount (OID), the annualized yield works out to 4.36%.

If we ask, “What is the expected annual rate of return on this 25-year zero-coupon Treasury?” the answer is obviously “4.36%.” Now the fact that it is a zero-coupon bond and that an investor has to wait 25 years to get his principal plus interest, are certainly relevant. But we wouldn’t use these facts to lower the reported yield on the asset. No, we would simply warn that it was subject to interest rate risk, would tie up funds for a quarter-century, etc. The yield is still 4.36% on this particular asset.

Scenario 2: Getting Paid From the Will

Suppose now that a middle-aged man with substantial assets needs some cash. Rather than sell off some of his real estate or stocks, he instead wants to borrow against them, posting these assets as collateral. So he cuts a deal with a lender, saying, “I will borrow $3,440 from you, in exchange for paying you back $10,000 when I die. That is, I will revise my will, listing that I owe you $10,000 to be paid upon my death. However, in the event that I live beyond 25 years from now, I will simply pay you $10,000 myself at that time.”

In this scenario, what would we report as the expected rate of return on this asset, from the lender’s perspective? Assuming that the borrower is good for his debt, the worst the return can be is an annual yield of 4.36%. That’s what the lender earns if the borrower lives another 25 years and at the end of the wait, writes a check for $10,000 to the lender.

However, if the borrower happens to die sooner than 25 years after taking the loan, then the lender earns a return that is higher than the floor of 4.36%. For example, suppose the borrower takes the $3,440 and dies a year later. Then the $10,000 payment from the will works out to a whopping 191% annual return. If the borrower dies after two years, then the annualized return falls to 70%, which is still phenomenal. If the borrower dies in the third year, the annualized return is 43%. The compound average return rate steadily falls as the borrower lives longer and longer, hitting the floor of 4.36% at year 25.

Now in this new scenario, if someone asks, “What is the expected return to this lender?” the answer is, “Higher than 4.36%.” (With more information about the age and health of the borrower, we could give a more precise answer.) Yes, there are still issues of tying the money up and interest rate risk, and this asset is less liquid than a zero-coupon Treasury, but when we ask about the rate of return in this scenario, clearly it is higher than the 4.36% we quoted for the zero-coupon Treasury in Scenario 1.

Scenario 3: The Borrower Adds a Cash-Out Option

Finally, suppose that our hypothetical lender in Scenario 2 is concerned about the lack of liquidity. After all, if he needed cash and had to sell his 25-year zero-coupon Treasury in the year (say) 2035, he would be able to find plenty of buyers. The interest rate risk means that he might have to sell at a lower price than he originally expected (if we assume interest rates rise after he has locked in his money), but it wouldn’t be hard to actually sell the zero-coupon Treasury.

However, there is not nearly a deep secondary market for the arrangement with the middle-aged man who wants to schedule the payback out of his will. If the lender in this case needs cash, who is going to want to buy the unorthodox IOU issued by the borrower?

To help alleviate this problem, suppose that the borrower also agrees that, should the lender choose, he can turn the IOU back in ahead of time, for a cash payment that is smaller than the promised $10,000. Further, the borrower puts into their contract the rising level of payback amounts, according to the time it is requested. For example, suppose the borrower agrees that if ten years go by and the borrower is still alive, the lender can turn in the IOU and receive an early payment of $3,918. (In light of the original $3,440 loan, that payback in year 10 amounts to an annualized return of 1.31%.)

Now here’s where things get interesting. What should we report as the expected rate of return on this new asset? Back in Scenario 2, we had no doubt that the rate of return was higher than 4.36%. What we have here in Scenario 3 is clearly a better asset, from the point of view of the lender: It does exactly the same thing as in Scenario 2, except on top of that, there are more options available to the lender. That is, rather than having to get either $10,000 when the borrower dies, or 25 years have passed—whichever comes first—in this final scenario, the lender still gets those two possibilities, but on top of that, he also has the possibility of cashing in the IOU while the borrower is still alive before the 25 years have passed.

One perfectly accurate way to describe this new arrangement is to say that the asset in Scenario 3 is just like the asset in Scenario 2, except that it is more liquid and less subject to interest rate risk. Specifically, if the lender wants to cash out early, in Scenario 2 he would have had to go find a buyer for this unusual IOU, and if interest rates had risen in the interim he would possibly have to take a huge hit on what he could sell it for.

Both of these downsides are mitigated in Scenario 3. If the lender needs to cash out early, he always has the guaranteed buyer in the form of the original borrower. Hence the IOU is now more liquid than in Scenario 2. Furthermore, by specifying ahead of time the (steadily rising) price at which the IOU would be repurchased, the new arrangement limits the harm of rising interest rates. The “firesale” price can’t go below the contractually specified buy-back price, no matter how high interest rates may have risen since the original loan occurred.

So because we were quite certain that the rate of return in Scenario 2 was at least 4.36%, and the asset has all of the same features in Scenario 3 except that it has more liquidity and is less vulnerable to interest rate risk, it would be odd to say that its expected rate of return is lower than 4.36%.

Surprise! Welcome to Whole Life

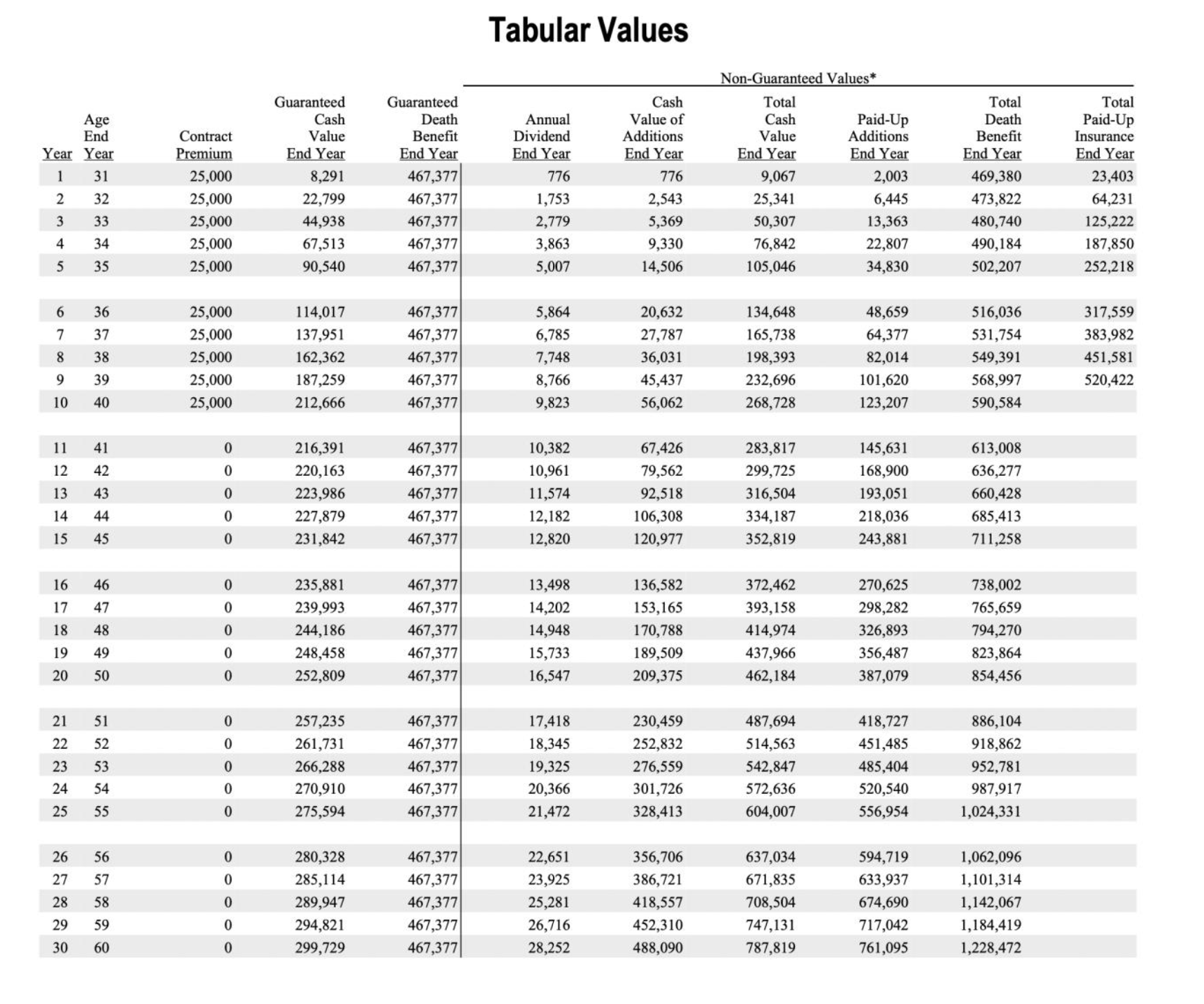

The reader may have guessed where this was going: By the time we got to Scenario 3, we were describing the cash properties of a Whole Life policy. Specifically, consider the following 10-pay policy on a hypothetical 30-year-old male:

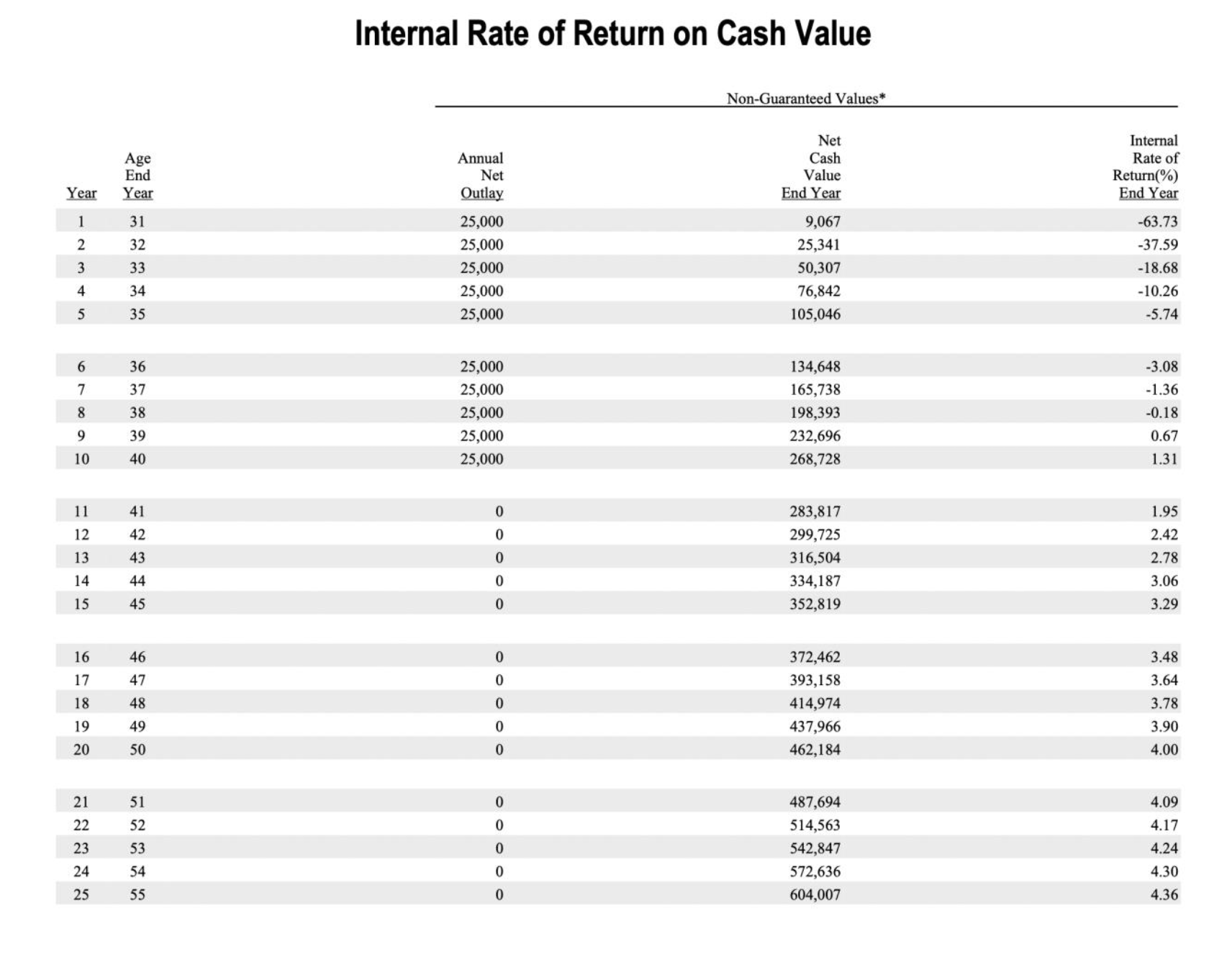

In the policy above, the contract calls for $25,000 annual premium payments, for the first ten years. The initial death benefit is $469,380 (assuming the projected dividends occur). Now look at the cumulative, annualized internal rate of return on the cash surrender value through the first 25 years:

Now the reader can see why I picked such oddly specific numbers in the scenarios above. Here we see that twenty-five years into the policy, the IRR on the cash surrender value is 4.36%. However, if we only go ten years into the policy, then the IRR is only 1.31%.

When people castigate the “abysmal returns” of Whole Life, they have in mind that someone surrenders the policy early on. That’s the only way to make sense of Dave Ramsey’s claims that Whole Life earns 1.0 to 1.5%. He is referring to the cash-out option that is in-built into Whole Life policies.

But remember our discussion above. When we were considering Scenarios 2 and 3, it seemed wrong to deflate our estimated rate of return on the asset, merely because we made it more liquid and less sensitive to interest rate risk. So why are we not giving Whole Life the same treatment? For the policy illustrated above, if the man holds it at least 25 years, then he enjoys an annualized return of 4.36%.

But wait, it gets even beyter. In our Scenarios 2 and 3, we were talking about the face $10,000 being paid back upon death or twenty-five years, whichever came first. But for the Whole Life policy illustrated above, if the man waits 25 years, he can surrender the policy for $604,007.

Yet if the man dies before that, his beneficiary may get more than $604,007. For example, if he dies in Year 16, his beneficiary receives $738,002. So if it seemed wrong to “ding” the IOU in Scenario 3 just for giving more benefits to the borrower, likewise it seems wrong to ding a Whole Life policy—when reporting on its expected return—because it gives extra options of liquidity and protection from interest rate risk.

Conclusion

By thinking through scenarios involving other long-dated assets, we see that the traditional approach to reporting on the expected return of Whole Life policies is biased against this asset. Consider: If there were no option to surrender the policy back to the carrier earlier than Year 25, for the policy above we would say its expected rate of return was at least 4.36%, and that it suffered from the downside of illiquidity and extreme interest rate risk. That is exactly how finance websites discuss zero-coupon long-dated Treasuries.

But paradoxically, because Whole Life policies give more options—which serve to boost liquidity and reduce interest rate risk—the financial world has decided to report the rate of return on the early cash-out scenarios. Whole Life policies therefore get a bad rap on their presumed returns simply because they are more advantageous than other types of long-dated fixed-income assets, such as zero-coupon Treasuries.

NOTE: This article was released 24 hours earlier on the Infinite Banking (IB) 3.0 - The Future of Finance Facebook Group

Dr. Robert P. Murphy is the Chief Economist at infineo, bridging together Whole Life insurance policies and digital blockchain-based issuance.

Twitter: @infineogroup, @BobMurphyEcon

Linkedin: infineo group, Robert Murphy

Youtube: infineo group

To learn more about infineo, please visit the infineo website

.png?width=520&height=294&name=New%20Article%20Thumbnails%20(17).png)

Comments