Comparing Whole Life to “Buy Term & Invest the Difference” Part 1 of 2

As a proponent of using customized Whole Life insurance policies as the ideal cash management vehicle (see my previous post explaining how it works), I often encounter the objection that “buy term and invest the difference” is superior. However, the typical glib demonstration (such as offered by Dave Ramsey, for example) is fraught with unfair assumptions that stack the deck against Whole Life.

In this two-part series, I want to show how, as an economist, I would go about fairly evaluating the two rival strategies. As we’ll see, each approach has its pros and cons. My point isn’t to say Whole Life is great and term is bad but to show how an individual can rationally think through the actual tradeoffs.

What “Buy Term & Invest the Difference” Means

For a given individual and specified level of death benefit coverage, a Whole Life policy will cost far more than a term life insurance policy. So people like Dave Ramsey argue that Whole Life inefficiently tries to achieve two goals at the same time: providing death benefit coverage and an investment vehicle. Instead, Ramsey argues, a person should independently buy as much life insurance as he needs to replace his income for a set time horizon (say, 20 or 30 years) and put the savings — the extra money needed to fund the Whole Life policy — into a separate vehicle, such as a tax-advantaged mutual fund tied to the stock market.

In this way, Ramsey thinks you get the best of both worlds: You’re covered in case you die prematurely so that your spouse and kids (if applicable) are taken care of, and you’re building your retirement fund in assets that grow at an attractive rate. In the long run, you end up with far more money (Ramsey would conclude) by buying term and investing the difference, rather than foolishly plopping huge premium payments into an archaic Whole Life policy.

Setting Up Our Head-to-Head Comparison

There’s a lot of material I need to cover to do this topic justice, so in Part 1, I want to explain the two strategies our hypothetical man could consider. Then, in Part 2, we will take this framework and run it through a series of metrics to see how either strategy looks better or worse.

Our hypothetical individual is a 25-year-old male nonsmoker in good health. He wants to have at least $1 million in death benefit coverage in force for at least 30 years, and he would like to have a growing pool of liquid funds available as “savings” and, in the long run, to fund his retirement. We are going to show two different strategies that achieve these objectives.

Strategy 1: Whole Life Policy Customized for Rapid Cash Growth

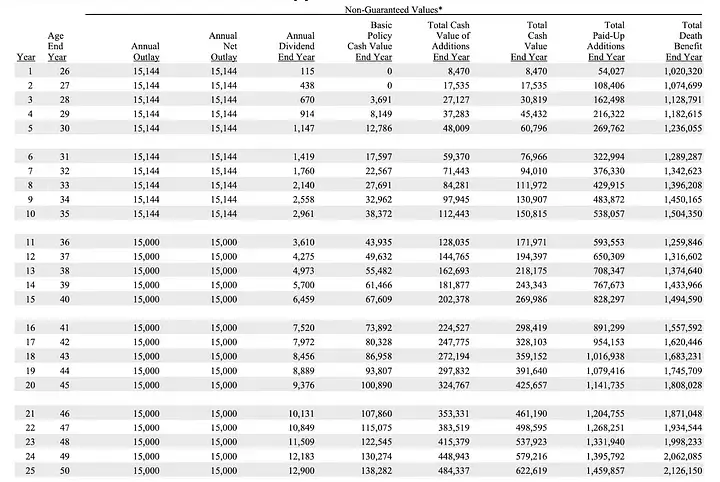

The first strategy is a Whole Life policy, designed in a customized fashion for rapid cash accumulation. (Of course, my colleagues at infineo are experts in providing households and businesses with Whole Life policies tailored to their specific circumstances.) Specifically, the basic chassis is a Whole Life policy with $15,000 of annual total premium going in, split 40/60 between a base premium and what’s called a Paid Up Additions (PUA) rider. For our purposes in this article, I can’t dwell more on what the PUA is except to say that it buys additional death benefit coverage and makes the cash value grow more rapidly than in a policy where all of the premium went into the base.

Now in order to prevent the policy from becoming a Modified Endowment Contract (MEC), which wouldn’t be the end of the world but negates some of the tax advantages of using a Whole Life policy, we also have a ten-year term rider on the basic Whole Life policy. The premium on the term rider is $144 per year. Any dividends that the policy generates are reinvested into the policy to buy more paid-up additional insurance.

After the 30th year (when the individual is age 55), the Whole Life policy is throwing off enough annual dividends to cover the contractual premium payment, and so we assume the man no longer puts in money out-of-pocket to keep the policy going.

The following screenshot shows what this setup looks like, in terms of the illustration generated by the home office software, for the first 25 years:

Strategy 2: Term Life Insurance Policy (30 Years) and Safe, Liquid Side Fund

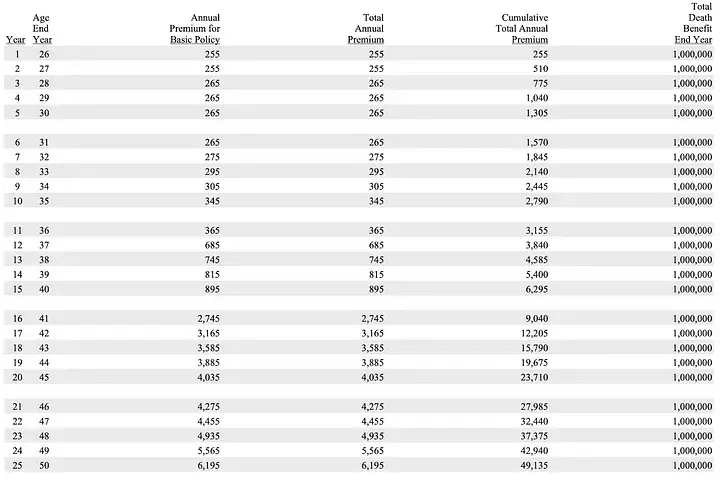

Since our first strategy pinned down the annual cashflows coming from our hypothetical man — namely, $15,144 for the first ten years, then $15,000 for the following twenty — we assume the same out-of-pocket contributions for the Buy Term & Invest the Difference approach. We have $1 million in death benefit coverage in a 30-year term policy, which has a level premium of $705 annually. (We are, of course, using the same hypothetical man and the same life insurance company software to generate the two different policies for our analysis.)

Before proceeding, let me unpack that number. At first blush, it seems that Dave Ramsey is right! Yikes, the Whole Life policy had a premium of $15,144 in Year 1 to get (a little more than) $1 million in death benefit coverage, whereas using the same company, the same guy can get $1 million in coverage on a 30-year term policy for only $705 a year. What explains this? Is it the huge commissions going to the Whole Life salesman?

No, the fundamental difference is that a Whole Life policy, for our 25-year-old man, is effectively a 96-year term policy. That’s because the Whole Life policy will be in force up through age 121, at which point it endows or matures and pays the “death benefit” to the man if he still happens to be alive.

So the reason the Whole Life policy is so much more expensive is that it contains a very valuable continuation option that the 30-year-term policy lacks. One way to appreciate this is to look at what the one-year renewable premiums are for the same man and $1 million in death benefit coverage:

Now, the premium charge of $705 for a fixed-level 30-year policy is put in context. In the early years, that amount is “overcharging” our hypothetical man because the pure cost of insurance is so low when he’s in his late 20s or early 30s. But beyond age 39, charging only $705 annually for $1 million in death benefit coverage is “undercharging” him. Intuitively, on the front end, the carrier takes in more money than it needs for the rare case of a 28-year-old dying, and it invests the excess in assets to help pay the death benefit claims later on when people in that cohort are still only paying $705 annually for policies that have a much higher pure cost of insurance.

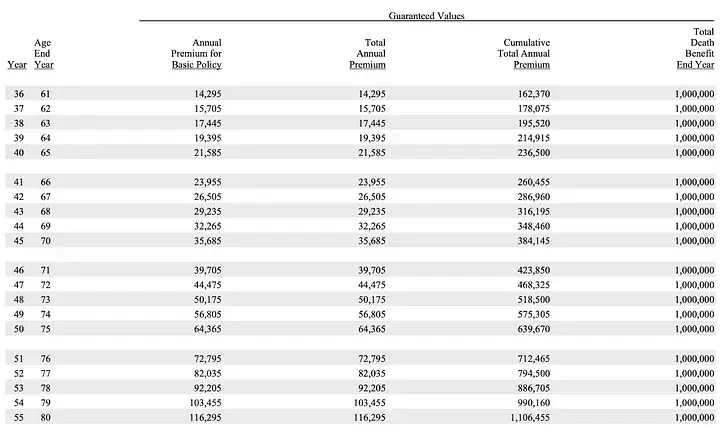

To see how rapidly the annual cost of term insurance rises with age, look at these figures from further down in this illustration:

To make sure the reader understands: The above excerpt shows that at, say, Age 75, our hypothetical man would have to pay $64,365 just that year to maintain $1 million in death benefit coverage. This is why people who take the Dave Ramsey approach when they are young and put in place term life insurance end up “self-insuring” down the road — which is the same thing as saying they no longer have life insurance. If you haven’t set up a permanent life insurance policy early on, it can be very expensive to put in place when you’re older.

Explaining the “Side Fund”

After that digression into insurance pricing, we can return to our scenario: With the difference each year (between what the first approach requires for the Whole Life policy and the $705 that the second approach needs for the much cheaper 30-year term policy), Strategy 2 makes annual contributions (through Year 30) into a side fund. I think it is entirely fair to assume that this side fund grows at an after-tax rate of 3.5 percent.

Now, here is where some readers may object to my assumption, but I want to explain my rationale. First of all, I am saying after-tax because the man needs to be able to access this money without penalty. He can do so with a Whole Life plan by taking out a “policy loan” with the Cash Surrender Value serving as collateral. So it wouldn’t be apples-to-apples if we had him, in Strategy 2, plopping his money into a tax-qualified plan that carries stiff penalties for early withdrawal.

In contrast, the internal growth in a Whole Life policy isn’t taxed, at least if you handle the policy properly. (In this article, I can’t get into the specifics, but this is part of the issue with the MEC that I described earlier.) So, the growth in the Cash Surrender Value that you see in the first screenshot above is effectively after-tax and should be compared with after-tax returns on rival strategies.

In addition, this “side fund” needs to be extremely safe and liquid. The Cash Surrender Value in the Whole Life policy is guaranteed to grow at a (modest) pace and, in practice, will typically pay dividends yearly (though the dividends aren’t guaranteed). And when a dividend is issued, that raises the CSV to a new, higher floor, from which the policy can never go down. I must stress that the cash available in a Whole Life policy is immune not just from market risk but also interest rate risk. So even someone building up a “side fund” of, say, 20-year Treasuries would potentially have a more volatile asset because — as Silicon Valley Bank recently illustrated — rising interest rates can make long-term Treasuries plummet in market value.

Consequently, to mimic the dependability and accessibility of the Cash Surrender Value in a Whole Life policy, the side fund for Strategy 2 has to be something like a bank savings account, short-term bank CDs, or Treasuries with a short duration. And yes, right now, T-bills are yielding attractive returns, but most people expect them to come down in the near future (which is partly why the yield curve is still inverted).

For all of these reasons, I think it is entirely reasonable to assume an after-tax rate of return of 3.5 percent on our “side fund” for Strategy 2.

Now that I’ve given the context and explained the framework for our head-to-head comparison, in next week’s post, I will show how each of the strategies performs. To end your suspense, we will see that each has its pros and cons.

To reiterate, my point here is not to tell readers that term life insurance is bad, but rather to show that the glib demonstrations from people like Dave Ramsey — which do purport to show that Whole Life is bad — are completely useless, because they overlook several fundamental issues that must be included in an evenhanded assessment. I will spell out all of these considerations next week in Part 2 of this series.

NOTE: This article was released 24 hours earlier on the IBC Infinite Banking Users Group on Facebook.

Dr. Robert P. Murphy is the Chief Economist at infineo, bridging together Whole Life insurance policies and digital blockchain-based issuance.

FIND PART 2 OF 2 HERE

.png?width=520&height=294&name=New%20Article%20Thumbnails%20(34).png)

.png?width=520&height=294&name=New%20Article%20Thumbnails%20(20).png)

Comments