The Internal Rate of Return on Whole Life Insurance

On these pages, I have written extensively on using Whole Life insurance for cash management (see here for a primer), but I have never directly tackled the issue of the internal rate of return on such a policy. Critics like Dave Ramsey will say that the return on Whole Life is 1 to 1.5 percent. When contrasted with a mutual fund tied to the stock market that Ramsey (very optimistically) says will earn 11 percent annually for many decades into the future, it looks like only a fool would put his money in Whole Life.

Yet, as we’ll see, Ramsey is simply wrong if we take a long-run view, particularly if one designs the Whole Life policy for rapid cash accumulation. In this post, I’ll walk through two illustrations, first showing a plain vanilla Whole Life policy and then a similar policy optimized for cash growth.

Plain Vanilla Whole Life

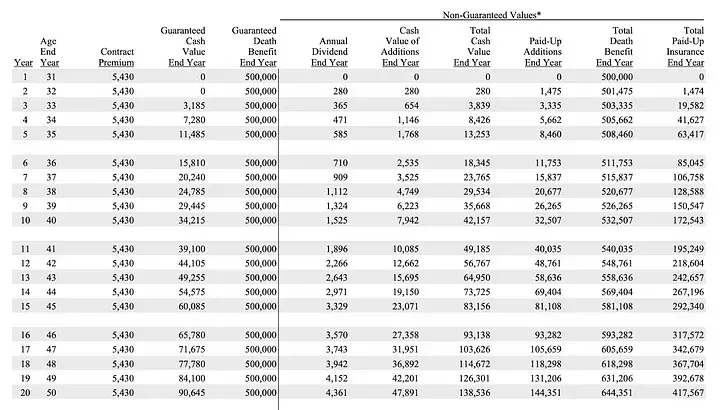

Here is a real-world illustration from a large mutual company showing a Whole Life policy with $500,000 in initial death benefit (which grows over time due to dividends buying more “paid up” insurance) on a nonsmoking 30-year-old male:

The right-hand side shows what will happen if the dividends are paid according to projections. Although these are, as the label indicates, not guaranteed, they are very dependable in practice. I should also report that in my experience working with such policies over the last 10 years, they do perform according to the projections that I am reviewing in this post.

So, just to make sure the reader understands how to read the above table, the contractual premium on this “plain vanilla” Whole Life policy is $5,430 per year. That locks in the initial $500k death benefit. At the end of (say) Year 5, when the man is 35, the Cash Surrender Value of the policy is guaranteed to be at least $11,485, but in practice, with dividends each year, it will probably be $13,253. As the name suggests, the CSV is what the man would get if he surrendered the policy, but it is also the collateral for a policy loan if the man wants access to cash without collapsing the policy.

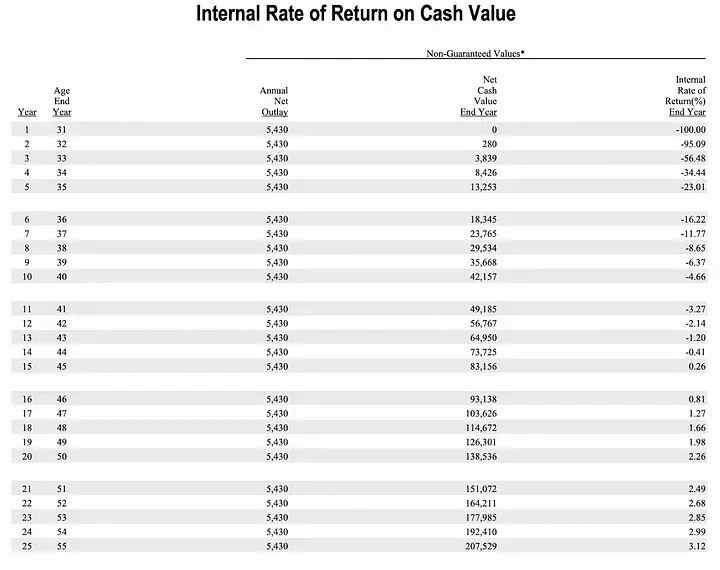

With this plain vanilla WL policy, here are the projected internal rates of return on the Cash Surrender Value for the first 25 years, according to the non-guaranteed projections:

So it’s true. You definitely don’t want to take out a Whole Life policy if you think you may have to surrender it early on. But even with this plain vanilla structure, by 25 years into it the cumulative annualized internal rate of return on the premium payments has risen to a respectable 3.12 percent.

Keep in mind that this internal growth is not being taxed, and if handled properly, the policyholder can access it without incurring tax liability. In addition, the principal of the Cash Surrender Value is extremely safe and liquid, even more so than a fund of long-term Treasuries (which suffer from interest rate risk). In a previous post, I explained the proper way to think about the rate of return on a Whole Life policy’s Cash Surrender Value because this is a special asset with many desirable properties that a simple comparison of rates may obscure.

But things are even more attractive if we tweak the design of our Whole Life policy, which we do in the next section.

Adding a Paid-Up Additions Rider

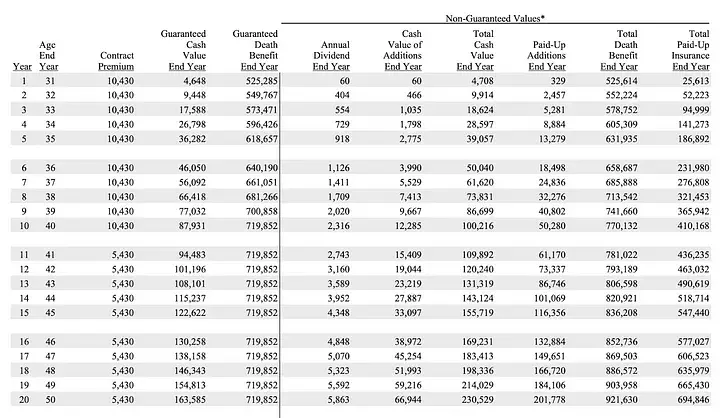

We now show the illustration if we start with the same basic policy but append on top of it the ability for the man to add an additional $5,000 annually for the first 10 years. Each of these payments is a one-shot burst that buys additional death benefit (without further commitment to premium payments). Here’s what it now looks like:

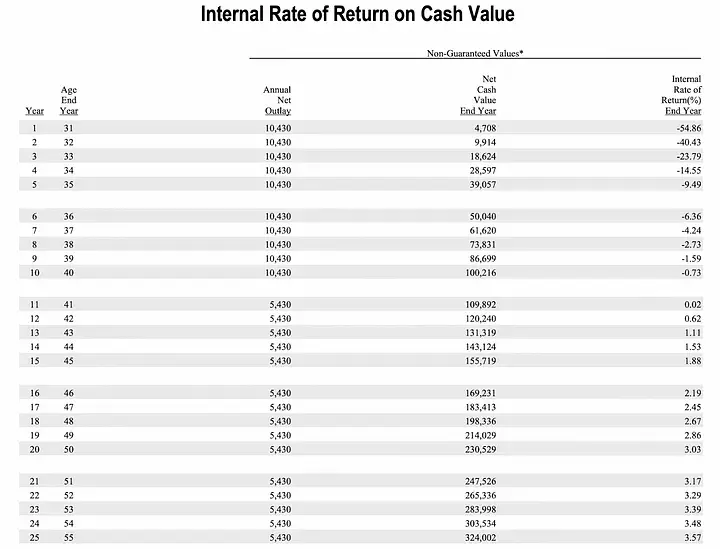

With the above approach, of course, the man has more death benefit at any given year, but in addition, the extra payments show up immediately in the Cash Surrender Value. This advances the schedule of internal rates of return, as I show in the next table:

As this final excerpt indicates, when we append a cash accumulation feature on the policy twenty-five years into it, the cumulative annualized rate of return is a respectable 3.57 percent. (It maxes out at 4.3 percent when the man is 78 years old.)

I want to be crystal clear: These figures for rates of return are cumulative. The year-by-year figures are higher once we get many years into the policy. What the figures above show are the annualized rates of return over the entire life of the policy to date.

As a final reminder, for all practical purposes, these rates of return should be compared with after-tax rates on other assets. In that respect, the implicit long-run rate of return on the second policy is closer to 6.8 percent because that’s the pre-tax return you would have to earn on a rival asset in order to receive an after-tax return of 4.3 percent (assuming a marginal tax rate of 37 percent).

To be sure, an effective 6.8 percent return on an asset is not something to write home about, but when it’s generated by an asset that is incredibly safe and liquid and suffers no market or interest rate risk, then the case for Whole Life becomes much more compelling. At the very least, we can be sure that Dave Ramsey’s statistics are not the full story by any stretch.

NOTE: This article was released 24 hours earlier on the IBC Infinite Banking Users Group on Facebook.

Dr. Robert P. Murphy is the Chief Economist at infineo, bridging together Whole Life insurance policies and digital blockchain-based issuance.

.png?width=520&height=294&name=New%20Article%20Thumbnails%20(17).png)

.png?width=520&height=294&name=New%20Article%20Thumbnails%20(26).png)

Comments